Father of our Modern Music

Heinrich Schütz...

…was the first German composer of European stature.

Italy knows of me / not to mention all of Germany

A while back Denmark got to know me /

Also Sweden offered me her hand /

That carried up high my fame /

On Schütz by superintendent D. Georg Lehmann (1616-1699)

Heinrich Schütz was already regarded during his lifetime as the “very best Teutonic composer”. But his work and influence went far beyond that: he set the course for musical progress in Central Europe. First of all, he allowed styles and influences from several countries and regions to permeate his work.

… looked with Galileo through the telescope.

Second, because he adeptly networked with the European intellectual, scientific, and cultural elite of his time, he therefore contributed not only to the advancement of musical development, but by and large to European intellectual history.

In 1610, as Schütz resided in Venice, Galileo Galilei first introduced his telescope. (German)

… translated words into music.

The quintessential legacy of Heinrich Schütz, and at the same time the source of his relevance today, can be found in his artistic usage of the word. The word is a central component in his work. His unique usage of text lies in the fact that he is not content with capturing the rational meaning of words and their grammatical contexts. Rather, he is capable of rendering things that go above and beyond what we are able to express with human speech, thereby enlivening them.

The inexpressible and rationally incomprehensible take shape in his music.

This is achieved in equal measures in settings of biblical texts as well as in the creation of secular madrigals.

Heinrich Schütz reveals an inner vision of the word in a highly artistic form.

Martin Flämig (choir master), 1985

… wed Italian music with German poetry.

Weil dero Zeit in Italia, zwar ein hochberümbter, aber doch zimlich alter Musicus undt Componist [Giovanni Gabrieli] noch am leben were, So sollte Ich nicht verabseumen, denselbigen auch zu hören, undt etwas von Ihm zu ergreiffen ...

Heinrich Schütz, memorial from 1651

Gabrieli! Immortal gods, what a great man that was!

Heinrich Schütz, preface to the Symphoniaesacrae I, 1629

… created musical sermons of unforeseen clarity.

This phenomenon [the relationship between word and tone in Schütz’s music] did not have anything to do with mood or atmosphere, but is instead a process of a deep internalization and spiritualization, realized with an economy and concentration of material that is heretofore unparalleled and exemplary.

Although the genesis of the music of Heinrich Schütz dates back more than three centuries, it is still relevant to us today. It exists far away from all hints of historicism and conservation, it exists as a piece of the past that speaks powerfully to us and infuses the word with a new and intense corporeality.

Martin Flämig (choir master), 1985

… gave a century its musical form.

This recording of the Dresden Chamber Chorus under the direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann appeared within the framework of the complete recordings of Schütz (Vol. 1: Carus 83,232).

We thank the publisher Carus for their permission.

… is the parensnostraemusicae, the father of our modern music.

I have occupied myself very strongly with Webern. Bartók was always present. Perhaps also Stravinsky.

Schönberg and Berg have actually remained alien to me. Additionally, I found roots in the Passions of Schütz, as well as with Monteverdi and Mussorgsky.

György Kurtág (Hungarian composer), in an interview from 2000

György Kurtág: Schütz Transcriptions of the 7 Last Words, for 4-hand piano [Track 1]

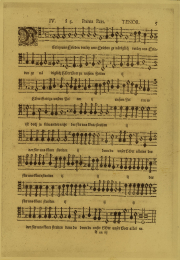

![The beginning of the upper voice from “Ich hebe meine Augen auf” [I lift up my eyes], SWV 31 The beginning of the upper voice from “Ich hebe meine Augen auf” [I lift up my eyes], SWV 31](/ger-wAssets/img/weblication/wThumbnails/IMSLP366548-PMLP315696-schutz_psalmen_davids_C1-24-bearb-ad418d880e9c576gcd6e3011e6898870.jpg)